What’s a Mobile Web App?

A mobile web app is an application that is built with the core client web technologies of HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, and is specifically designed for mobile devices. Helping mobile web apps get a bit of attention are the trends toward HTML5 and CSS3—the latest “versions” of two of the technologies. We explore both HTML5 and CSS3 in detail in the book, along with a lot of JavaScript.

JavaScript is the language that many developers love to hate. Some don’t even regard it as a programming language at all. However, JavaScript is here for the long haul, and is likely to be one of the most in demand skillsets for the next five years.

2. Getting Started

Welcome to the wonderful world of web app development for Android. Over the course of the book we will walk through the process of building mobile web apps. While targeted primarily at Android, most (if not all) of the code will work just as well on Chrome OS. Actually, the reusability of the application code will go beyond Chrome OS—the code from this book should be able to run on any device that provides a WebKit-based browser. If you aren’t familiar with WebKit or Chrome OS at this stage, don’t worry—you will be by the end of the book.

In this chapter, we will go through a few topics at a high level so you can start building applications as quickly as possible:

- An overview of the platform capabilities of Android

- Which of those capabilities we can access through the web browser (either by default or by using bridging frameworks such as PhoneGap)

- Configuring a development environment for coding the samples in this book and your own applications

- An overview of the tools that come with the Android development kit, and some supporting tools to assist you in building web apps

2.1 Understanding Android Platform Capabilities

The Android operating system (OS) was designed as a generic OS for mobile devices (including smartphones and tablet PCs). The plan was that Android would serve multiple device manufacturers as their device OS, which the manufacturers could then customize and build upon. For the most part this vision has been realized, and a number of manufacturers have built devices that ship with Android installed and have also become part of the Open Handset Alliance ( http://openhandsetalliance.com).

Android, however, is not the only mobile OS available, and this means that a native Android application would have to be rewritten to support another (non-Android) mobile device. This leads to having to manage the ongoing development of mobile applications for each of the platforms that you wish to support. While the large companies of the world can afford to do this, it can be difficult for a smaller organization or startup. Here in lies the attraction of developing mobile web apps—write the application code once and have it work on multiple devices.

This section of the book will outline the current features of the Android OS, and if relevant whether you can access that functionality when building web applications.

For those who would prefer a summary of the system capabilities and what you can actually access via the browser or a bridging framework, then head straight to Table 1– 2, toward the end of this section.

BRIDGING FRAMEWORKS

A bridging framework provides developers a technique for building web applications that can be deployed to mobile devices. The framework also provides access to portions of the native device capabilities (such as the accelerometer and camera) through a wrapper (usually JavaScript) to the native API.

During the course of the book, we will work through some examples that use PhoneGap ( http://phonegap.com) to bridge to some of this native functionality. While PhoneGap was one of the first, there are many more bridging frameworks available. In this book, though, we focus on PhoneGap, as it provides a simple and lightweight approach for wrapping a mobile web application for native deployment.

For more information on the various mobile web app frameworks, I have written a couple of different blog posts on the topic. In particular, the following post has some great comments from contributors on the projects that help to show their areas of strength: http://distractable.net/coding/iphone- android-web-application-frameworks.

While I would have loved to talk more about each in this book, the focus here is on building mobileweb applications. From my perspective, these are applications that can be deployed to the Web and accessed via a device’s browser. The addition of a bridging framework should be an optional extra rather than a requirement. Given this particular use case, PhoneGap is a clear winner.

Device Connectivity

While as consumers we are all probably starting to take the connectivity options of our own mobile devices for granted, it’s important not to do this as a mobile developer (web app or native). If mobile applications are built assuming that a connection to the Web is always available, then this limits the usefulness of an application when connectivity is limited—which is more often than you might think.

Understanding that your application will have varying levels of connectivity at different times is very important for creating an application that gives a satisfying user experience at all times.

In very simple terms, a mobile device can have three levels of connectivity from a web perspective:

- A high-bandwidth connection (e.g., WiFi)

- A lower-bandwidth connection (e.g., 3G)

- Limited or no connectivity (offline)

At present, when building a pure web app, you can really only detect whether you have connectivity or not (without actually attempting downloads or the like to test connection speed). This is different from building native Android applications, as these applications can access native APIs that provide information regarding the device’s current connection type and quality.

In Chapter 5, we will investigate features in the HTML5 API for enabling your applications to work well offline, and in Chapter 9 we’ll explore examples using bridging frameworks to access some of the native connectivity detection.

Touch

One of the features that helped the current breed of mobile devices break away from the old is the touch interface. Depending on the version of Android, at a native level you will either have access to multitouch events or just single-touch events. Web apps, on the other hand, only allow access to single-touch events at this stage.

NOTE: Not having multitouch event support for web apps certainly gives native applications an

edge when it comes to application UI implementation. This will almost certainly change in the future, but for some time we will likely have a situation where some Android devices support

multitouch for web apps and others don’t.

It will be important at least for the next couple of years to always code primarily for single-touch, and offer improved functionality (time permitting) for those devices that support multitouch

events in the web browser.

We will start exploring touch events in some depth in Chapter 7.

Geolocation

The Android OS supports geographical location detection through various different implementations, including GPS (Global Positioning System) and cell-tower triangulation, and additionally Internet services that use techniques such as IP sniffing to determine location. At a native API level, geolocation is implemented in the android.location package (see

http://developer.android.com/reference/android/location/package-summary.html), and most bridging frameworks expose this functionality from the native API.

Since HTML5 is gaining acceptance and has been partially implemented (full implementation will come once the specification is finalized in the next couple of years), we can also access location information directly in the browser, without the need for a bridging framework. This is done by using the HTML5 Geolocation API ( www.w3.org/TR/geolocation-API). For more information on the HTML5 Geolocation API, see Chapter 6.

Hardware Sensors

One of the coolest things about modern smartphones is that they come equipped with a range of hardware sensors, and as technology becomes more pervasive this is only going to increase. One of the most widespread sensors currently is the three-axis accelerometer, which allows developers to write software that tracks user interaction in innovative ways. The list of hardware sensors that the Android OS can currently interact with goes beyond the accelerometer, however, and a quick visit to the current hardware sensor API reference for native development reveals an impressive list of sensors that are already supported in the native API (see

http://developer.android.com/reference/android/hardware/Sensor.html). Table 1–1 lists the various sensors and provides information on whether access to the sensor is currently supported with the bridging framework PhoneGap. If you are not familiar with one of the sensors listed, then Wikipedia has some excellent information – simply search on the sensor name. Note that while the Android SDK (software development kit) supports a number of hardware sensors, most are not accessible via mobile web apps (yet).

Table 1–1. Sensors Supported by the Android SDK

Sensor

|

PhoneGap Support

|

Accelerometer

|

Yes

|

Gyroscope

|

No

|

Light

|

No

|

Magnetic field

|

No

|

Orientation

|

Yes

|

Pressure

|

No

|

Proximity

|

No

|

Temperature

|

Yes

|

One of the most compelling arguments to go with native development over web development is to gain access to the vast array of sensors that will continue to be added to mobile devices as technology progresses. While definitely a valid argument, building a web app in conjunction with a bridging framework can allow you to access some of the more commonly used and available sensors.

Additionally, PhoneGap is an open source framework, and the ability to write plug-ins is provided (although hard to find good information on), so it’s definitely possible to access additional sensors.

Local Databases and Storage

Mobile devices have for a long time supported local storage in one form or another, but in more recent times we have started to see standardized techniques (and technology selection) for implementing storage. Certainly at a native API level, Android implements support for SQLite ( http://sqlite.org) through the android.database.sqlite package

SQLite is quickly becoming the de facto standard for embedded databases, and this is true when it comes to implementing local storage and databases for web technologies. Having access to a lightweight database such as SQLite on the client makes it possible to create applications that can both store and cache location copies of information that might normally be stored on a remote server.

Two new, in-progress HTML5 standards provide mechanisms for persisting data without needing to interact with any external services apart from JavaScript. These new APIs, HTML5 Web Storage ( http://dev.w3.org/html5/webstorage) and Web SQL Database ( http://dev.w3.org/html5/webdatabase), provide some excellent tools to help make your applications work in offline situations. We explore these APIs in some depth in Chapter 3.

Camera Support

Before touch became one of the primary sought-after features for mobile devices, having a reasonable camera was certainly something that influenced a purchase decision. This is reflected in the variety of native applications that actually make use of the camera. At a native level, access to the camera is implemented through the

android.hardware.Camera class (see

http://developer.android.com/reference/android/hardware/Camera.html); however, it is not yet accessible in the browser—but the HTML Media Capture specification is in progress (see www.w3.org/TR/capture-api).

Until such time that the specification is finalized, however, bridging frameworks can provide web applications access to the camera and picture library on the device.

Messaging and Push Notifications

In Android 2.2, a service called Cloud to Device Messaging (C2DM)

( http://code.google.com/android/c2dm/index.html) has been implemented at the native level. This service allows native developers to register their applications for what are commonly known as push notifications, whereby a mobile user will be notified when something is new or has changed.

It will be some time before push notifications are implemented in browsers, as a working group has only recently been announced to discuss and provide a recommendation on this particular area (see www.w3.org/2010/06/notification-charter).

Unfortunately, with C2DM being reasonably new, it will probably be some time before the bridging frameworks implement this for Android.

WebKit Web Browser

The Android OS implements a WebKit-based browser. WebKit ( http://webkit.org) is an open source browser engine that has reached a notable level of adoption for desktop and mobile browsers alike. The WebKit engine powers many popular browsers like Chrome and Safari on the desktop, and mobile Safari and the native Android browser in mobile (to name a few). This alone is a great reason to build web applications for mobile rather than native applications. As both Android and the iPhone implement a native WebKit browser (Mobile Safari is WebKit at its core), you can target both devices very simply if you consider WebKit as your common denominator.

Why is having WebKit in common so important? Given HTML5 and CSS3 are both still emerging specifications, it will probably be a couple of years before web standards are concrete and mobile browsers all behave in a consistent way. For now, having WebKit as a common element between the two dominant consumer smartphone platforms is a huge advantage. As developers, we can build applications that make use of the components of HTML5 that are starting to stabilize (and are thus being implemented in more progressive browser engines, such as WebKit), and actually have a good chance of making those applications work on both an Android handset and an iPhone. Try doing that with either native Android Java code or iPhone Objective-C code.

NOTE: Adoption of WebKit as the “mobile browser of choice” appears to be gaining momentum.

Research In Motion (RIM), the company responsible for BlackBerry, has adopted WebKit and HTML5 in its new BlackBerry Torch. This is good news for mobile web application developers, and I believe shows the future is in cross-platform web development rather than the current

trend of native development.

Process Management

Process management is handled similarly on Android and iOS devices since Apple’s release of iOS 4; however, prior to that there was a fairly significant difference between the way Android and iPhone applications behaved when a user “exited” them. On the iPhone, once you left an application, it essentially stopped running—which meant there really wasn’t any ability to do anything in the background. On Android, however, if a user left an application (including a web application) without quitting, it would continue to execute in the background.

To validate this, we ran the following code on an Android handset to ensure that requests were still coming through while the application (in this case the browser) was not the active application.

<html>

<body>

<script type="text/javascript"> setInterval(function() {

var image = new Image();

image.src = "images/" + new Date().getTime() + ".png"; }, 1000);

</script>

</body>

</html>

Using the JavaScript setInterval call in this context means that an image request (for an image that doesn’t exist) is issued every second. When the code runs, that image request is made to the web server every second (or thereabouts) regardless of whether the web browser is the active application or not. Additionally, as the browser on Android supports multiple windows being open at once, the request will continue to execute even if the browser is active but a different window is selected as the current window.

Having this kind of background processing ability provides developers some excellent opportunities. It is, however, important to make sure our applications are built in such a way that when in the background, applications aren’t downloading unnecessary information or consuming excessive battery power.

Android OS Feature Summary

Table 1–2 shows a matrix of device features, the Android version from which they are supported, and whether they can be accessed in the browser. In some cases the browser support column uses the term bridge. This refers to the use of bridging frameworks (such as PhoneGap, Rhodes, etc.) to expose native device functionality to the browser.

Table 1–2. Android OS Features and Browser Accessibility Matrix

Device Feature

|

OS Version Support

|

Browser Access

|

Connectivity detection

|

_ 1.5

|

Bridge

|

Geolocation (GPS)

|

_ 1.5

|

Yes

|

Hardware sensors

|

_ 1.5

|

Bridge*

|

Touch screen and touch events

|

_ 1.5

|

Partial

|

Local storage and databases

|

_ 1.5

|

Yes

|

Messaging/notifications

|

_ 2.2

|

No

|

Camera

|

_ 1.5

|

Bridge

|

2.2 Preparing the Development Environment

Now that you have a high-level understanding of what you can do on the Android platform with regard to web apps, let’s move on to getting our development environment set up so we can start developing applications in the next chapter.

There are multiple approaches that can be taken when putting together an effective development environment for mobile web apps on Android. The basic components of the setup outlined in this section are a text editor, a web server, and an Android emulator (or handset). You could, however, choose to use an IDE like Eclipse instead

(see http://eclipse.org).

Eclipse is an IDE that is tailored for Java development, and the Android team offers native Android development tools for Eclipse. If you are working with both web and native Android development, you may prefer to continue with the Eclipse environment— and if this is the case, there is nothing in this book that will preclude you from doing so.

NOTE: While there are many merits to using a full-featured IDE for web development, I personally

prefer using lightweight and separate tools. Using a standalone web server and accessing the content from your device’s browser will allow you to more easily test multiple devices

simultaneously without the overhead that might be imposed by using tools provided within the IDE.

Additionally, if I decide to focus on another mobile device as a primary development target, I can continue to use the same tool set to develop for that platform. I anticipate that we will see two or

three dominant players and a long trail of perhaps ten-plus platforms in the mobile space, so

having an approach that works across devices is definitely appealing.

Text Editors and Working Directories

Any text editor that you are comfortable using will serve you more than adequately when writing web apps for Android. If you really aren’t sure which text editor you want to use, then Wikipedia (as usual) has an excellent comparison list (see

With your trusty text editor now beside you, it’s time to set up the directory that you are going to work from as you progress through this book. The actual location of the directory is completely up to you, but I would recommend building a folder structure similar to the following, as this will assist you in working through the examples:

§ PROJECT_WORKING_DIR

· css

· img

· js

· snippets

Reusable CSS, image, and JavaScript resources will be stored in the css, img, and js folders, respectively. As we progress through the book, we will build folders for each chapter under the snippets directory for that chapter.

Web Server

Having a web server serving your application code as you develop it really helps streamline your development process. Throughout the book we will be working primarily with client-side technologies, so our requirements for a web server are quite lightweight. This means pretty much any web server will do the job, so if you already have a web server that you wish to work with, that is absolutely fine.

For those who don’t, however, we will quickly walk through getting a lightweight web server called Mongoose running on Windows, Mac OS, and Linux. Mongoose is extremely simple to get running; just follow the installation guide for your platform as described following (there may be some differences depending on your individual configuration).

Mongoose on Windows

Firstly, download the Mongoose standalone executable (mongoose-2.8.exe at the time of writing) from the project downloads page: http://code.google.com/p/mongoose/

downloads/list.

There is an installer package available, but installing Mongoose as a service won’t be as simple as using the standalone executable. Once the file has been downloaded, put the executable file somewhere on your path (recommended but not required), and then skip to the “Running Mongoose” section of this chapter.

Mongoose on Mac OS

The simplest way to install Mongoose on Mac OS is by using MacPorts ( www.macports.org). If you don’t already have MacPorts installed, install it now by following the simple instructions provided on the MacPorts web site.

With MacPorts installed, to install Mongoose run the following command:

sudo port install mongoose

If MacPorts is installed correctly, this should download, build, and install Mongoose, after which it should be ready for your immediate use. Proceed to the “Running Mongoose” section of this chapter.

Mongoose on Linux

With Mongoose being so lightweight, it is actually very simple to build Mongoose from source on most Linux systems. The following instructions are for systems running

Ubuntu, but only minor modifications will be required to adapt this to another Linux system.

Firstly, download the Mongoose source from wget http://mongoose.googlecode.com/files/mongoose-2.8.tgz.

Next uncompress the downloaded archive file:

tar xvzf mongoose-2.8.tgz

Change directory to the Mongoose source directory:

cd mongoose

And then run make targeting Linux:

make linux

You will now be able to run Mongoose using the full path of the Mongoose executable. If you would prefer to be able to run Mongoose without specifying the full path, then copy the Mongoose executable into a path such as /usr/local/bin:

sudo cp mongoose /usr/local/bin/

That’s it—you can now run Mongoose.

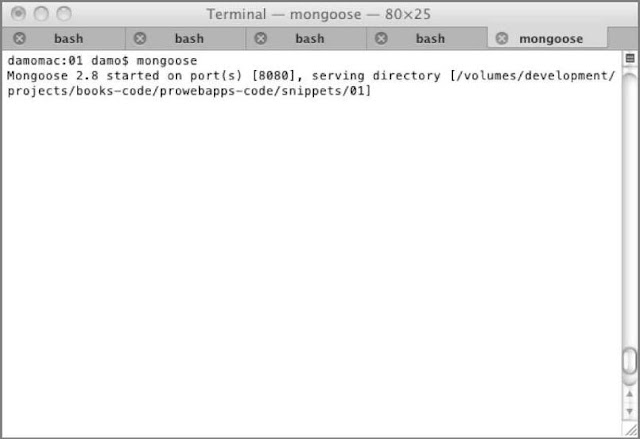

Running Mongoose

Running Mongoose is refreshingly simple. Configuration defaults are sensible, so running mongoose from the command line produces a web server that runs and serves that folder as the web root.

Additionally, Mongoose will bind to all of the IP addresses assigned to your computer, which means that you will be able to browse from other devices on your network using the IP address (or one of the IP addresses) of the machine you are running Mongoose from.

Let’s try running Mongoose now. Open up a command prompt/terminal window and then change directory to PROJECT_WORKING_ DIR, which you set up in the previous step. If Mongoose is located on your path, you will be able to run mongoose from the command line; and if not, then you will need to run it using its absolute path. Either way, once you have run the command (no command-line options required), you should then be able to browse to http://localhost:8080/ and see the directory file list of the folders you set up earlier (as shown in Figure 1–1).

Figure 1–1. With Mongoose running, you should see a directory list of folders created earlier.

Alternative Approaches

You can also copy files across to an emulated SD card image and load them from the image by using the file://sdcard/<filelocation> syntax. If you are interested in more information on how to create SD card images and copy files to and from them, I recommend checking out the information at the following URL:

Emulator

To test the samples, you will either need an Android handset or the Android emulator that comes bundled with the SDK. If you don’t already have the SDK, you can download it from http://developer.android.com/sdk. Follow the instructions on the Android site, with the exception of installing Eclipse and the ADT plug-in (unless you already have it installed and are comfortable using it). Once you have the Android SDK installed, the emulator and associated tools can be found in the tools directory of the SDK installation directory.

Creating an Android Virtual Device

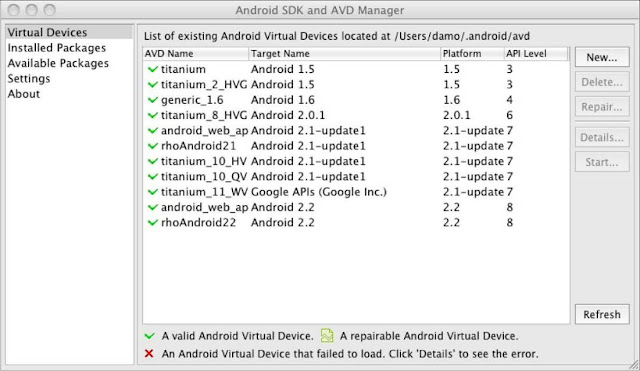

Creating an Android Virtual Device (AVD) is straightforward when using the GUI tools that are provided as part of the Android SDK. First, locate the android executable and run it. The location of the executable will depend on the SDK installation path, but essentially you are looking for the file android (android.exe on Windows) within the tools folder of the SDK installation directory. This will launch the Android SDK and AVD Manager application, which is shown in Figure 1–2.

Figure 1–2. The Android SDK and AVD Manager

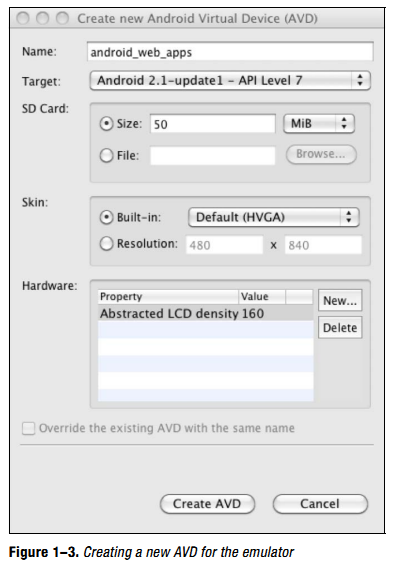

Here we will create a device for running our samples. Nothing too fancy is required, just the standard emulator running with version 2.1 of the SDK or greater. Press the Add button to start creating the image. Once you have done this, you should see a screen similar to the one shown in Figure 1–3.

You need to provide at least three pieces of information when creating a new AVD file:

· The name of the device (no spaces are allowed). Here we are creating a device called “android_web_apps.” This is the name that is used when launching the emulator from the command line.

· The target Android API we are developing for. At the time of writing, both Android OS versions 2.1 and 2.2 have the highest levels of

market penetration, with 1.5 and 1.6 now in the minority (see http://developer.android.com/resources/dashboard/platform- versions.html). For the examples in the book, we will primarily work with a version 2.1 emulator. By using a version 2.1 emulator rather than a version 2.2 emulator, we can make sure our code will work on both versions of the OS—but it is still important to test on as many versions of the OS as possible.

· The size of the SD card. You can also specify an existing SD card image if you want to, but that’s not required for running through the samples in the book. I’d recommend just specifying a size of 50MB or thereabouts.

Other information, such as the skin value (somewhat synonymous with screen resolution), will be automatically populated based on the API version selection, but you can tweak these options if desired. All of the samples in the book have been designed with a standard mobile device screen size of 320_480, so I’d recommend working with that.

NOTE: Some of the examples in the book illustrate the difference between standard dpi (dots per

inch) and high dpi, and how that will impact your applications. For these samples, you will need an AVD that is configured with a higher screen resolution than standard. When configuring this device, select a resolution such as WVGA800 (or similar) to emulate a device with a high device

dpi.

Starting the Emulator

Once the AVD has been created, you can then start the device by pressing the start button, which is displayed to the right of the device images. You will be prompted with a couple of options (as shown in Figure 1–4), but in general selecting the defaults is fine (although wiping user data can sometimes be very useful for getting back to a clean slate).

Figure 1–4. Launching a new virtual device for our emulator using the AVD Manager

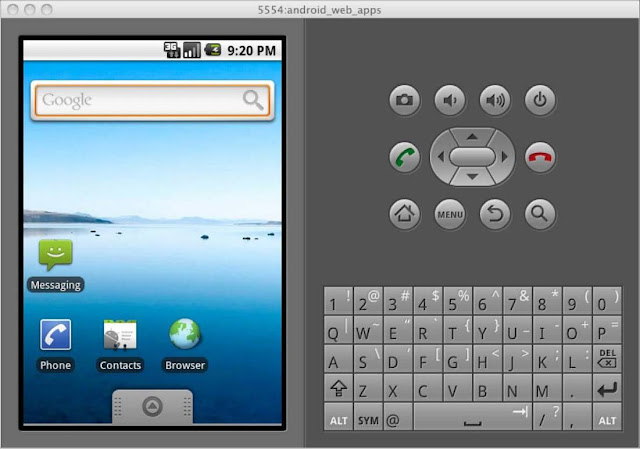

Once the emulator has started, a screen similar to Figure 1–5 will be displayed, indicating that the Android emulator is starting.

Figure 1–5. The Android emulator starting—a good time to get some coffee

Be aware that the emulator does take quite a long time to load, so once you’ve got it loaded, try to avoid closing it. When it’s finally loaded, you will see an Android home screen like the one shown in Figure 1–6.

Figure 1–6. The Android emulator has loaded successfully; open the browser to get started.

From the home screen, run the browser and you will be able to access the local web server that you configured previously.

2.3 Hello World

Before we get into the working through the specifics of mobile web applications and sites in the next chapter, let’s make sure our development environment is set up correctly with a very simple Hello World example.

First we will create a very simple HTML file that we will use to validate that we can view our development files in the mobile browser on our Android device:

<html>

<style type="text/css">

body {font: 4em Arial;}

</style>

<body> Hello World </body>

</html>

Save the preceding code sample to a file named helloworld.html, and then access the directory in which that file is stored from your terminal or command prompt. Run Mongoose (either using the absolute installation path or just mongoose, depending on how you installed it and your path configuration) from that location.

Figure 1–7 shows a screenshot of some example command-line output you will see if Mongoose has been run correctly.

Figure 1–7. Mongoose web server example output showing the port and directory that content is being served from.

While Mongoose will inform you of the port it is running on, you will also need to find the IP address of your machine so that you’re able to browse the server from both the emulator and an actual Android device connected to your local network via WiFi. One of the simplest ways to determine your IP address is through the use of the ifconfig or ipconfig commands on Mac OS/Linux and Windows, respectively. If you are unfamiliar with the technique then the following links may be of assistance:

- Linux: linux-ip.net/html/tools-ifconfig.html

Armed with the knowledge of your IP address, you will now be able to view your test page in the emulator (or your Android device). Figure 1–8 shows example screen captures from the Android browser, showing both browsing to the helloworld.html file that we created and what is displayed in the browser as a result.

NOTE: While you may be accustomed to using localhost (or 127.0.0.1) when browsing a

development webserver when operating on your own machine, when you are working with an Android emulator (or device) you will need to access the webserver via the IP of your machine on

your local network. Mongoose is very helpful in this regard and will happily serve web pages

from any IP (including 127.0.0.1) that is associated with your machine.

Now that you have successfully created a Hello World example, it is time to move on to actually learning what makes a web application or site mobile. This is the topic for the next chapter.

NOTE: To keep things simple, in this example we ran Mongoose from the same directory that the

helloworld.html file was stored in. For the remainder of the examples, we will be working in a slightly more complicated directory structure to ensure that we can reuse certain files between

chapters. For instance, in the example source code repository on GitHub ( http://github.com/sidelab/prowebapps-code), this file is stored in the following location: /snippets/01/helloworld.html.

This is the kind of directory structure that will be used for the rest of the book, with each chapter’s code samples being stored within a directory under the snippets directory. Some larger examples, such as the geospatial game covered in Chapters 9 through 11, will use a

variation on this structure, but this is the general rule.

In future examples, Mongoose will be run from the directory above snippets. This in turn means that the path you will use to browse the majority of future examples will match the

Screenshot run testing on windows xp:

2.4 Summary

This chapter covered the basic capabilities of an Android device and what can be achieved in web apps as opposed to native apps. This included looking at what is available via standard browser support, as well as through using bridging frameworks to extend native functionality to a web browser embedded in a native application.

We also walked through the very simple requirements for running a development environment for building Android web apps. Additionally, we took a preliminary look at some of the tools that will help you debug your code as you work through the samples in this book and later you create your own applications.

In the next chapter, we will look at some of the simple techniques that are used to create mobile-friendly web pages and the foundation pieces of a mobile web app. We’ll begin with some simple standalone examples, but quickly move on to working through a practical example: building a simple to-do list application. We will continue to explore and build this in Chapters 3 and 4 also.

LINKS

LINKS

Nguồn Pro Android Web Apps

0 comments:

Post a Comment